Here’s a glimpse into my passion for storytelling and how I believe its an inseparable part of being a disciple on the run. May we be blessed in our storied lives in Christ! Sharing excerpts from an interview Sean Madden Brown of Woodside Priory School conducted with me in 2011.

How did you get interested in focusing on stories as a way of fostering learning and communication in the workplace?

I have always been driven to understand how we connect to ourselves and others. I marveled at the prowess of my father’s conducting. I felt an electricity connecting composer with conductor, orchestra with conductor, and audience with orchestra. I witnessed the power of my mother’s voice bringing music alive with the artistry of caressing words with her breath and spirit. And peak experiences on stage as a child and peak performances as a competitive fencer offered me other glimpses into this mysterious realm.

I’ll never forget one of my first classes at Brandeis University. One of the requirements was a two-semester humanities class. I must confess I was less than excited about the class. It looked as though it was going to be a waste of time. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

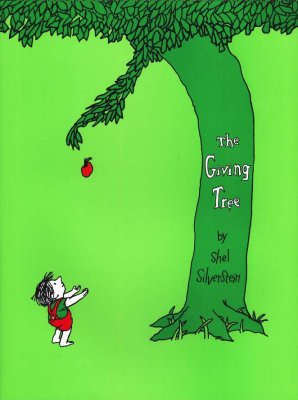

I ended up in a class being taught by Professor Luis Yglesias titled “Imagining Who We Are.” Professor Yglesias began his class by reading Shel Silverstein’s story, The Giving Tree. It’s a simple story about a boy and a tree growing up together. The tree is always there for the boy. In the end the tree even gives its life so that the boy can build a home for himself with its wood.

As he finished, the entire class sighed sentimentally. But Professor Yglesias did not stop. He returned to the first page of the story and reread it to us. Without editorializing, using only his mischievous eyes and the nuances of his voice, he brought the story alive in a completely different way.

Imagine our surprise when we realized that The Giving Tree was not necessarily a sweet story. The boy could as easily be seen as narcissistic and exploitive; the tree knew how to give, but the boy only took.

The same story that had greatly moved the class was now responsible for catalyzing emotions of outrage and disbelief. Some of us were angry for having our idealized vision of the boy and the tree shattered; some of us were incensed by the social message of selfishness and the abuse of nature implied by the story.

Professor Yglesias was not making a political comment. Nor was he trying to espouse postmodern assertions of relativism. He was simply giving us a wake-up call, and he was activating our imaginations. He was guiding us to actively connect to the story, and he was asking us to challenge our habitual response to a story we had heard many times. We were being led to discover the heart of what stories are all about. My life has not been the same since that day.

Professor Luis Yglesias introduced me to the power of imagination. He poured a foundation of reflection fashioned out of stories, narratives, sense giving and sense making. I had been looking for a framework for examining how we connect to ourselves and others. Today, I feel blessed to have had this initial intellectual inquiry deepened, by realizing this is yet another vehicle of the Holy Spirit.

Stories are a tool for reflection and insight. Stories graciously offer us the opportunity to look at ourselves and the world around us in new ways.

Stories are fundamental to the way we communicate and learn. They are the most efficient way of storing, retrieving, and conveying information. Since story hearing requires active participation by the listener, stories are the most profoundly social form of human interaction and communication.

What is it about stories that make them an effective means of bridging differences in people?

We seldom know the “real story” behind someone’s feelings, beliefs, or actions. Worse yet, we do not make the effort to discover their story. Convinced of our opinions we prefer to keep our mental world neat and orderly by staying focused on our perspective rather than entertaining another point of view. While these natural proclivities of our mind are assets intended by evolution to equip our species with the ability to act independently and decisively, they are also liabilities when it comes to relationships. When we actively listen to other people’s stories we do not need to abandon our ideas; instead we can enter a new frame of reference by reconstituting the story being shared with us in our minds and hearts. Stories allow us to move in and out of a different frame of references. We are in essence, “standing in someone else’s shoes.”

As we listen to each other’s stories it becomes possible to negotiate differences. More often than not, our conflicts are a function of not hearing and understanding one another. Spontaneous solutions and resolutions arise when we enter someone else’s frame of reference. Sharing our stories generates vivid pictures for others because when we listen actively we bring our experiences to their telling. Therefore, a bridge of understanding is constructed between two or more people.

When negotiating differences in either a conflict or decision-making process, it is essential to hear, appreciate, understand, and acknowledge all of the perspectives. It turns out that stories are the quickest way to gain important insights. We are inclined to rationally explain and justify our perspectives; however, there are always experiences, values, and beliefs behind perspectives. Stories shed light on these things and can reveal a whole host of hard-to-identify motivations, like fears and self-interests. Stories get to the heart of matters and help us imagine other perspectives.

What’s inherently difficult about negotiating differences is that when faced with two strong points of views, opinions, or ideas, there is always some validity to each of them. This can be paralyzing. If each point of view has some validity, how do you draw a fair conclusion? Think about how a trial works. Each side presents its story. A jury has to work through each side of the story. In the end, they synthesize all of the information and formulate a story of their own in order to make a decision.

Using stories as a way of negotiating differences or getting to the root cause of a problem works because, unlike reasoning, stories are not linear in nature. While the sequence of events in a story follows a logical order, the themes and messages contained in it allow our minds to entertain paradoxes. Through stories we can simultaneously hold multiple and conflicting points of view as being true and consider them all without one negating the other. This leads to a very rich experience, since our minds must open to a whole world of nuances.

When we actively listen to stories we are invited to enter a novel frame of reference. The story provides us with the material to work emotionally and logically with new information. Placing two or more viewpoints side by side offers us an opportunity to imagine a whole new set of possibilities previously hidden to us. The stories give us a safe and often depersonalized sand box to work out our differences. Arbitrators are excellent at helping people to consider conflicting points of view. There is a direct correlation between the success of a mutually satisfying outcome in arbitration and the degree to which people share and hear each other’s stories. Like arbitrators, managers can increase their effectiveness at negotiating differences by making time, and a safe space for people to tell their stories. Managers must use the experiences of people shared in the form of stories to engage them in conversations full of rich exchanges. The stories become participatory theaters where clashing ideas, competing desires and needs can be played out.

Do you ever feel a chasm between yourself and another person? Perhaps his point of view is so different from your own that you find it unthinkable to even entertain it. Like many of you I’m sure, I have sat through many meetings in which the ostensible subject is diversity among employees, for example, but in which most of the meeting is given over to celebrating similarities rather than recognizing the uniqueness of every individual—a uniqueness that goes beyond, race, ethnicity, gender, or creed. Differentiation is the key to survival. Millions of species would not be alive today were it not for Nature’s careful attention to differences. The question is how can we account for both similarity and difference? Stories can save the day.

Stories enable us to encompass multiple points of view simultaneously. Imagine a visitor from another country who is limited to traveling to only one or two locales. What sort of impression will he form of our country as a whole? Is it likely that he will have an accurate picture? He hasn’t been to enough places to have a good idea. Yet, whatever impressions he forms will be the basis for communicating his experiences and ideas to others. In a case like this, the visitor is likely to realize the limitation of his experience and how it may be effect his perception. He will probably be open to different perspectives since he realizes the limitations of his own. When a native of our country or a visitor with a different set of experiences shares with our traveler their stories, he is likely to expand the narrowness of his initial impressions and add the experiences recounted by others. The gap between the visitor’s experiences and someone else’s is bridged by stories.

If only it were always this easy. Our view of the world is crafted from lots of experiences we store in our minds as stories. These in turn help us form our values, beliefs, assumptions, and biases that guide our behavior. Listening to stories encourages us to reflect on our similarities, appreciate other perspectives, and negotiate our differences. It is amazing to watch how quickly conflicts can disappear when we take the time to hear and validate someone else’s side of the story. Consequently, a new story can often be created that incorporates parts of different stories to produce a new interpretive framework and a new understanding of available possibilities.

What makes an effective story?

An effective story is any one that incites insight within us and or between others. Are you drawn into the story? Does it move your heart? Does the story deepen or challenge your current understanding? Does the story spur you to imagine new possibilities? Does it beg you to reach outside of yourself to seek something that you alone cannot give yourself?

By their nature stories are fluid. Stories overlap memories with the context of the moment. I find stories in collages and clusters to be more truthful than pinning the entirety of a message in a single story. All the greatest stories are vast little universes with an orbit of small story fragments. The depth and veracity of stories is more easily perceived when scanning the pattern and intention of stories in proximity with one another. I am naturally distrustful of single isolated large perfect stories with clean beginning, middles, and ends and unmistakable story arcs. In many instances these stories have already been warped around the gravity of a pre-digested message. Stories are creative acts and furthermore I view them as co-creative stages on which themes, drama, and meanings emerge in a process of co-creation. The story is only one small part of the key. The decoding and collaborative sense making space generated by telling a story to trigger the stories of others is sacred. My experience has been that when this space opens up, storytelling and listening is authentic, deep, and responsive to the needs of the moment. The space falls apart when listening ceases and any one person returns to advancing a monocular agenda.

Do you draw on story archetypes, such as Jungian, when you consult with companies on the use of storytelling? If so, why are archetypes effective and how does one avoid stereotypes when using archetypes?

Stories are patterns. Nature and our mind work in patterns. Jung’s work is brilliant and archetypes can be an effective way to engage in sense making. Archetypes repeat and they can be found everywhere. However, I do not find it necessary to use them in my organizational work. It’s far more effective to have people create their own taxonomies and categories. Inevitably, there will be overlaps and similarities

Indexing is how we classify our experiences. The better the index the easier it is find information. The problem with an index is deciding what descriptors to use to classify our experiences. Indexes are further complicated by the fact everyone will chose different “key words,” or descriptors to classify their experiences. If we cannot access our experiences due to an inadequate index or one that does not match someone else’s, our experiences become dormant. They are left in the proverbial warehouse of our mind available to our unconscious but collecting dust. Effective communicators and learners naturally develop extensive indexing schemes. They draw upon lots of different experiences and can recall these experiences in the form of stories.

Stories require active listening because they are encrypted. Each listening demands our full and undivided imagination. Stories are most effective when we leverage their multi-layered nature. Stories harkens us to seek meaning and generate personal associations with them. Stories are not meant to be left in isolation. Meaning arises through a series of relationships. Each story is somehow tethered to another one and it is through this sea of associations that we generate meaning and behavior.

How does the power of storytelling affect our work and personal interpersonal relationships?

Stories obliterate barriers and put us in touch with ourselves and in connection with others. Imagine people deeply connecting with each other. This whole new level of communicating is a place in which active listening to each other, reflecting on our experiences, and synthesizing new insights from each other’s experiences are commonplace. You see, stories help people to commune with one another in surprising ways. By sharing stories we are better able to express and appreciate our differences. The social network of stories becomes the fabric for meaning to emerge. Think of stories as complex self-organizing systems. Our differentiated sets of experiences are integrated and tied together by the rich, fluid nature of stories. In this medium of stories, we create the foundation for building a true community of learners.

What is the most challenging aspect of your work?

Having people understand my work. I don’t sell a specific set of goods or services. I architect communication, learning and development strategies to support performance needs in an organization. It’s never the same; nor do I espouse any secret formula or methodology. I often never use the word, “story,” with my clients. Stories are just an essential and inseparable part of how I do what I do. I’ll exercise the trust of this special forum to admit that the real work is the work of the Holy Spirit. I show up and create a space of dialog. Through the power and grace of the Holy Spirit things happen. People trust one another and they open up to themselves and to each other. People become attuned to a greater set of possibilities offered by God’s infinite unconditional love for us.

What advice would you give for current Priory students and parents?

Cherish each moment. The Priory is a unique ecosystem. You are being nourished and cared for in mind, heart, spirit, and body in ways that you will be hard pressed to find in such abundance as they are at the Priory. There are subtle ways that defy simple explanations that I have been formed by the Priory. Don’t underestimate the unique blessings of the monastic’s community daily rhythm of pray, the Holy Sacrifice of the mass, and their committed devotion to imitate Christ’s life as imperfect, fallible humans. We need to ask ourselves how can we be witnesses of God’s unconditional love embodied in the unique experience we had at the Priory?

Sail on your dreams and the dreams of others. So much is possible when we share our passions. Be sure to appreciate others’ talents. Celebrate their successes. Mostly there are great divides between ourselves and others due to our differences and our inability to extend our boundary of self to include someone else’s needs and fears. No one needs proof; only we do—and that is best found in how we creatively attend to actualizing our talents.

Tomorrow is no better than today, and circumstances may change 180 degrees—so be agile.

Being settled means being prepared to anticipate the Holy Spirit’s gift of the next creative moment.

What do you believe is the most serious issue facing the human race today?

We have forgotten that we are beggars in God’s kingdom. All of our technology all of our independence, all of our wonderful assertions of free will and creativity that have been given to us have intoxicated us with illusions of who we are. We are adopted sons and daughters dependent upon the grace and mercy of God in all things. Can we return to a sense of awe and wonder? Might we be firmly planted in this world while submitting ourselves to the will of God – working each day to bear fruit from the application of our gifts? If we can act as the hands, eyes, and mouth of our Lord, we will emerge in and out of issues, tensions and problems with a deeper sense of who we are and a greater capacity to cultivate our inheritance of lasting peace.

This holy mystery of the dance between our freedom and God’s will is not one I ever expect to fully understand. My faith guides me today to recognize that God touches everything. He works in every detail from the seemingly miniscule to the monumental. He is sculpting our spirits every moment.